Mike Browne worships his new job as a tour pro so much, he says he would not change a thing, not even having his leg amputated. Tim Taylor tells the uplifting and inspirational story of a 42-year-old army veteran who as recently as 2014 had never hit a golf ball in his life.

Mike Browne took up golf by chance after his leg was amputated. Having lost his job in the Royal Artillery he was desperately in search of anything to find a social life, having attempted to kill himself, which failed in comic circumstances.

In two and a half years, he progressed from a novice going round the course in 148 strokes to turning professional. He has since competed on seven pro tours, become a serial winner on the European Disabled Golf Association circuit and has six sponsors.

Mike says: “As mad as it sounds, golf has given me such a wonderful new life that I would go through it all again, even having my leg amputated.”

In 2014 he was trapped in the depths of a severe depression caused by the aftermath of the amputation. This followed a series of 22 failed operations after he smashed his left leg in a motorcycle accident in 2011.

Now he’s on a mission to convert as many people as possible to take up golf and insists: “This sport is a life-changer. In fact, it doesn’t matter if you’ve got a disability or not. Taking up golf changes you and brings out the true person you really are. At one stage, when things were really bad before I took up golf, I sat at home crying for three days in a row.”

It is six years since Mike, now 42 and with a playing professional’s attachment to the Long Sutton club in south Somerset, first gripped a club.

As mad as it sounds, golf has given me such a wonderful new life that I would go through it all again, even having my leg amputated.”

Last year he claimed the national disabled championships of France and Czechoslovakia and retained the South African title, which in 2018 he captured 12 shots clear of the field. Who is to say he would not have added to his haul in 2020 if Covid-19 had not been inflicted upon us all?

He has walked the same fairways at the same time as major champions Tiger Woods and Ian Woosnam and on regular tours, his record includes two top-six finishes on the Clutch Pro Tour, based in the south of England.

The motorbike accident ended his first job as an army corporal which saw him travelling the world for a different purpose.

“Following the amputation I was out of the military, stuck at home, doing nothing. I was going down a slippery slope. Who knows where I’d have been if it wasn’t for golf. This will seem weird . . . but now, even though I have lost a leg and went through a nightmare time before that, I feel as if I would not change anything the way it has all has turned out.

“Golf not only got me back into having a social life but also it changed my life, without a doubt. It might even have saved my life. Before I found golf, I had nothing. I didn’t know where I was going.”

Students of the mechanics of Mike’s fulfilling second career will be aware many PGA pros advise golfers to keep the front foot still on the tee and end the swing getting right up on your back toe, nicely balanced.

When Mike drives the ball, he uses the same unusual foot action as the U.S. Open champion Bryson DeChambeau. Unlike the Californian big hitter, Mike needs to because his prosthetic left leg is amputated above the knee.

He uses the ankle at the bottom of his prosthetic leg to make a rotation at impact which points his left toe forwards and flat. Mike points out this is the same method used by golfers who enter long drive competitions.

His has been a painstaking process. It is only in the past year Mike has trained his muscles enough to enable him to get fully up on his back toe and says he was relatively flat-footed before that.

“This is how I have had to adapt my body swing to generate more power. If it was not for my left foot coming out you would not know I have half a left leg and no knee. The rotation in the front ankle initiates the momentum which carries me around.

“It all enables me to get through the ball, rotate and get my left hip cleared. I have achieved a lot more balance over the past 12 months which has changed my swing massively.”

Golf has taken Mike to America, Australia, Dubai and Jordan and he admits to having fallen deeply in love with the sport: “I am living the dream. I have met so many amazing people and had so many fantastic experiences which I would not have enjoyed if I still had two legs.”

I just sort of turned it into my job straight away. I would go to the range at eight in the morning until half-four in the afternoon and treat it as a working day because that’s what I was used to doing in the military.

Now living in Salisbury, Wiltshire, Mike was brought up in the Somerset village of Street, near Glastonbury, and it was his family there who provided the emotional support he has needed more than anything else during his journey – father David, mother Wendy and sister Nicola.

“They did everything for me from my mum cooking my meals to them all just being there, doing the normal things in life that we all take for granted. I still have bad days but the bad days are getting better. I have been in really dark and deep places and at one stage I was on 52 tablets a day. I just didn’t want to be here.

“It’s a funny story, or well perhaps not, but I tried jumping out of the window and I could not get out because the brace on my leg caught round my neck, so my leg also saved my life. I had hit rock bottom but from then on it has just got better.

“All through my highs and lows and when I felt I had nowhere to go, my family were always there for me, as were close friends and many others who made my new life possible for me. I cannot thank everybody enough.”

As a youngster, Mike loved sport. While a pupil at Crispin School in Street, he was a flying left winger for the Somerset boys’ football team and during the 1990s won what was then called the British Schoolboys Motocross Association Championship three times in various age groups

He had reached European standard at motocross before joining the army at 19 and was on a training ride at Longmoor Military Camp in Hampshire in October 2011 when he smashed his leg and was taken to the Queen Alexandra Hospital in Cosham, Portsmouth.

Mike and other riders were doing repetitive laps on sand in preparation for the surface at a forthcoming event in Holland. As the track wore down, he did not notice a rock which had previously been buried. His ankle smacked into the rock at 30 mph, stopping him dead in his tracks.

“If you could imagine a bamboo stick when you crush it from the bottom up, well that was the state of my leg after I landed. Even so, I just thought that was it. I’ll be back in six weeks. Not a drama. I’ll go back to the job I was doing.”

In any list of the world’s most unfulfilled predictions, this outstrips even “Trump could never become president” as emanating from the cloudiest crystal ball imaginable. Mike spent five months in hospital during which time he endured 16 operations, followed by a further six operations after he had been discharged.

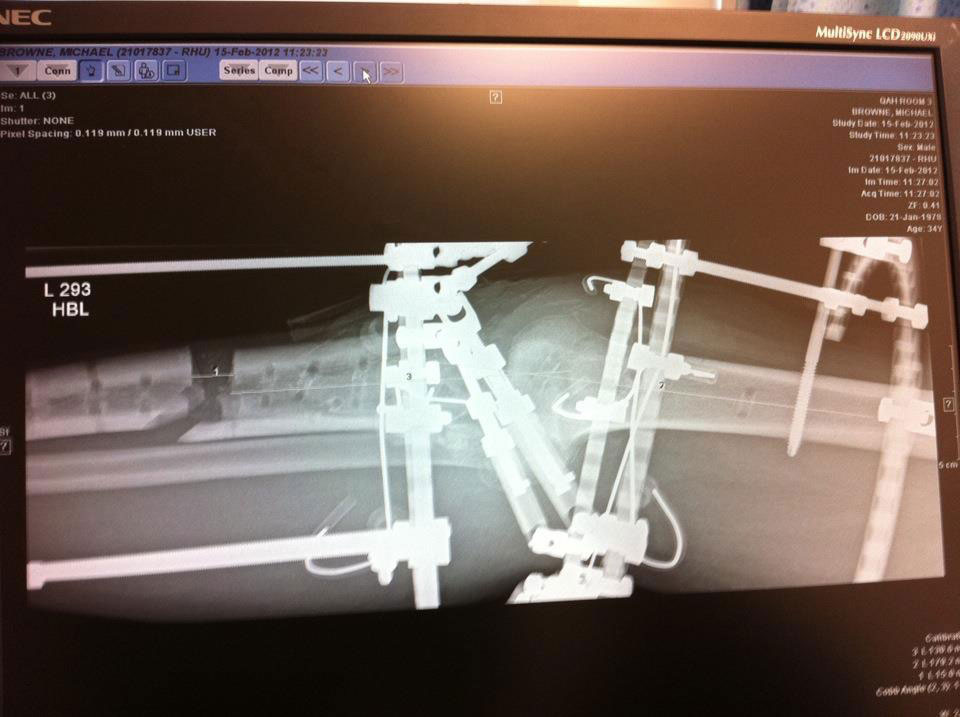

The intention had been to stretch his shinbone seven centimetres by means of daily one-millimetre adjustments. His leg was wrapped in that fame of a ring-like brace connected to 52 tensioned wires running through the unbroken part of the bone. So much for theory. In practice, he contracted a rare infection in the hospital which ate away all the muscle in his leg and he spent 19 months in pain.

In May 2013 Mike decided the drastic solution was the only way forward. “I sat down with my surgeon on the first day of that month and said that I was having trouble living like I was. Because I had a straight leg, I couldn’t drive a car, couldn’t go on a plane, and couldn’t walk up and down steps. I made the decision there and then and it was an easy decision: ‘Right, let’s get rid of it’.

“On May 7, my leg was amputated. I woke up and after all that time the pain had gone. It was amazing. I know it sounds like a hard decision, having your leg amputated, but I’d been through absolute hell.”

After the successful amputation, he spent a year in Surrey at the Defence Medical Rehabilitation Centre at Headley Court. But even the peril of working in war zones had not prepared Mike to cope with the psychological trauma he was about to endure.

“The fact something was missing from me was hard to deal with. I didn’t really leave the house for about six months. I didn’t see anyone outside of the rehab I was doing There was a lot of stuff going on in my head.

“The physical side of what happened had not been as much of a big deal as the mental side. I lost my job as a soldier and I lost my partner – she could not handle it – but golf means I have gone from losing anything which meant anything to me to having an amazing existence of playing golf around the world.”

The possibility of playing the sport first crossed Mike’s mind after a rehabilitation session run by Help For Heroes at Tedworth House in Wiltshire. He spotted a poster advertising the On Course Foundation.

This is a charity which helps sick and injured service personnel to get their lives back on track through playing golf. The first step was a one-day taster beginners’ session and initially, the then disconsolate Mike set out looking for no more than friendship.

Crucial to the sport rapidly meaning a lot more than that to him was the input from the foundation’s PGA professionals, Alastair Barr and David “Dai” Llewellyn.

Alastair has coached a world No 1 in Luke Donald. Dai is the son of a Royal Marine and a European Tour winner who won the World Cup of Golf for Wales in 1987 in partnership with Ian Woosnam, four years before Woosie won the Masters.

Mike said: “Alastair and Dai taught me from ‘basic basic’, to where I am now. They give you the positives about your swing. They have also taught me everything I have learned so far about being a professional golfer as well.

“I just sort of turned it into my job straight away. I would go to the range at eight in the morning until half-four in the afternoon and treat it as a working day because that’s what I was used to doing in the military.

“I say I treated it like a job, but it never felt like work, because I loved it. It was either that or sit at home and feel sorry for myself and I certainly didn’t want to do that.”

Mike turned pro in September 2016. “I had been invited to play as an amateur in the Willow Classic on the European Senior Tour. I shot five-under for my three rounds and finished ahead of a lot of the blokes – including Ian Woosnam, which was a really proud moment. It planted a seed in my head about turning pro and I thought, ‘Yeah, why not? Let’s do it.’ “

Last year Mike met the biggest name in the game playing the ISPS Handa Disabled World Cup at Royal Melbourne. This was an event in which the disabled golfers got to share the course with main tour pros competing in the Presidents Cup, the America v Asias version of the Ryder Cup.

Players from both events mixed at the pre-tournament dinner and Mike got to meet Tiger Woods who said hello and told him: “Have a good week and enjoy yourself.” The following day Mike was in the group following the 15 times major winner and his playing partners round the course.

Mike made his professional debut in Spain on The Gecko Tour in October 2016. As well as the Clutch Pro Tour he has played the TP Tour in the UK, the Middle East and North Africa Tour, the Europro Tour, the Florida Pro Elite Tour and the Moonlight Tour, based around the Daytona, Tampa and Miami areas.

Between 2014 and 2018, Mike played in five successive Simpson Cups, the equivalent of the Ryder Cup for wounded and sick veterans contested between Great Britain and America. He captained the GB side on Long Island in New York in 2018 and played in a winning team once, in 2015 at Royal St George’s, venue for the 2021 Open Championship.

If you google Mike, you might spot a fanciful suggestion he could become the first amputee to play the European Tour. Sensibly, he has both feet on the ground even if one of them is part of a prosthetic leg.

In the real world, his No 1 ambition is to influence others, saying: “I can’t over-emphasise how important it is to try golf, whether you have anything physically or mentally wrong with you or not. Golf has got everything you need.”

If you have read this far down Mike’s story, you will have gathered he is as eloquent as he is resilient. So it’s no surprise he has sponsors in JT Lifestyle Homes of Luton, Bushnell, Mizuno, Skechers, Max Golf Protein and DogLeg Reaper Belts.

How he came to be sponsored by JT lends credibility to the old adage that, however cruelly fate can sometimes turn against you, there are other occasions on which you might make your own luck.

In 2018, Mike signed for the lowest score of his career, a nine-under 63 in the pouring rain at the Ashridge club in Berkhamsted. He played in the same charity Pro-Am team as JT’s owner, Jan Telenski, an unassuming if pioneering environmental industrialist.

Among Jan’s many successful businesses is AquaCity, a luxury health spa which uses heat from the sub-surface of the earth, in this instance a vast underground lake at Poprad, Slovakia.

It’s safe to say the man who carved his initials on the JT business and warmed up the tourist trade in Poprad knows a man with cahones when he sees one.